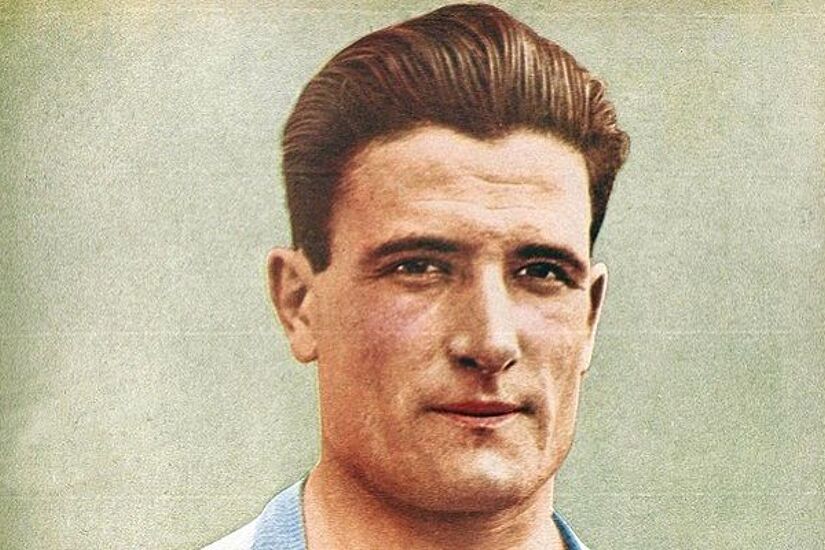

Doble Ancho: Luis Felipe Monti, the only man to play in two World Cup finals for two countries

Credit: Extratime Team (ETPhotos)

The FIFA World Cup, held every four years, is the most prestigious football tournament on the planet.

It dwarves the Olympics in terms of importance in the football world and regularly gains massive television audiences.

In 2018, over 3.6 billion tuned in to watch the most recent edition in Russia, which saw France claiming their second title.

To play in one is the pinnacle for any international footballer’s career.

While there have been numerous players over the years to play in multiple tournaments, and some even lucky enough to win multiple tournaments, there is one record out there still held by a single man.

Enter Luis Felipe Monti, the Argentinian born star who holds the honour as the only player to have played in two World Cup finals for two different countries.

He represented the country of birth in 1930 as Argentina were defeated in the inaugural tournament by neighbours Uruguay.

Four years later Monti went one better and won the tournament with Italy, who at the time were under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini.

Born in Buenos Aries in 1901 Monti began his football career at Club Atlético Huracán. In 1921, he won a league title in what proved to be his only season at the club.

The following season he moved on, first briefly to Boca Juniors for a three-month spell in which he didn’t play a single game and then to San Lorenzo.

Monti racked up 215 appearances over eight years for the Boedo side and developed the nickname ‘Doble Ancho’ (‘double wide’) due to the amount of the pitch he would regularly cover.

Those eight years proved to be a golden period for San Lorenzo they won back to back league titles in 1923 and 1924 and added another in 1927.

Naturally, it didn’t take long for Monti’s exerts to be noticed by national team coach Angel Vázquez and in 1924 he was called up for the first time.

Argentina was building a formidable team and in 1927 won the South American Championship and backed it up with a silver medal at the Amsterdam Olympics in ‘28.

La Albiceleste were progressing steadily, ready to peak for the inaugural World Cup finals in 1930 in Uruguay.

The first edition of the great tournament was not the same as we know it today. There was no qualification process and all of the FIFA affiliate nations were invited to take part, with 13 accepting.

Over half the countries competing were from the Americas, with Belgium, France, Romania, and Yugoslavia the only teams making the trip from Europe.

England, who would have been one of the strongest teams in the world, did not travel and had resigned as a member of FIFA at the time.

It is also said that Italy did not accept the offer in protest to being overlooked as potential hosts of the tournament.

Argentina started the tournament with a 1-0 victory over France with Monti scoring the only goal of the game.

They finished the group with a 100% record after comfortable wins against Mexico (6-3) and Chile (3-1) followed.

With the reduced format, qualifying from the group sent them into the semi-finals where La Albiceleste would face off against the USA.

A Monti goal meant the sides went in the break with the score 1-0. The first half was a violent affair and the USA lost midfielder Raphael Tracy after ten minutes to a broken leg.

The Argentine class showed in the second half and the Americans, unable to cope with their opponent’s superior skill and pace, leaked five more goals as the game finished 6-1.

Monti’s men would face Uruguay in the final. This was a sign of the strength of South American football at the time.

The outcome may indeed have been different if some stronger European nations such as Hungary and England had travelled, but there was no doubting that the two best teams at the tournament had got to the final.

Uruguay would have gone in as favourites after winning Olympic gold in both 1924 and 1928, beating Argentina in 1928 after a reply following a 1-1 draw.

The margins were fine and with Monti who was one of the top centre-halves in the world, Argentina fancied their chances.

However, luck would not be on the side of Argentina on the day they needed it most.

It had been reported in the lead up to the game that Monti had been struggling with an injury sustained earlier in the tournament.

Injured or not he played the game and instead another reported factor would go some way to deciding the outcome.

Uruguay started the game well and went ahead on 12 minutes with a goal from Pablo Dorado, which appeased the majority of the crowd in the Estadio Centenario.

Argentina fought back and, in the 20th minute, Carlos Peucelle shot across goal to equalize. Not content with that, the visitors then took the lead on the 37th minute with a goal from Huracán centre forward Guillermo Stábile.

This was Stábile’s eighth goal of the tournament and would mean he claimed the first-ever World Cup golden boot award.

With the two teams evenly matched and Argentina with a lead to hold on to, what happened in the second half seems even more peculiar. Uruguay bagged three goals and romped home as 4-2 winners.

It’s possible that with home advantage and Argentina’s energy levels waning after some tough games that La Celeste would have run out victors

However, in subsequent years Lorena Monti, granddaughter of Luis revealed how her grandfather spoke regularly about times he received threats to try and influence the outcome of games. The 1930 final was one such occasion.

“At half-time, when Argentina were leading 2-1, they said that if Argentina didn’t lose, they would kill my grandmother and my aunt,” she declared.

It’s difficult to know for sure the accuracy of the statement or how serious Monti would have taken it if it is true but surely any sane person would have erred on the side of caution and put his family over the game.

Argentina lost and, whether he knew it or not at the time, that would be his last major contribution with the nation of his birth.

Monti would go on to achieve his retribution but it would not be in sky blue and white. With professional football still in its infancy and no doubt, some feelings of angst with the outcome of the final, Monti would soon be on the move.

He was offered a deal to head to Italy to sign with Juventus. It was reported his wages would go from 200$ to $5000 per month, a life-changing amount at the time and one that proved too good to turn down.

A key broker in getting the deal done was none other than Benito Mussolini.

When Mussolini’s party Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF gained power in 1922 they set about uniting a previously divided series of city-states under one Italian identity.

Another strand of Mussolini’s plan for Italy was to improve the health and fitness of his citizens.

Sport, in general, seemed to flourish under him and it was the perfect outlet to replace the nationalism that can be garnered up during wartime.

With Italy hosting the 1934 finals, victory became paramount. In short, the better the performance the more belief the public would have in the regime to deliver.

As part of the deal that brought Monti to Turin, he took Italian citizenship and declared for the national side.

The Brazilian-born Anfilogino Guarisi and the Argentinean-born trio of Attilio Demaria, Enrique Guaita and Raimundo Orsi were the other members of the 1934 squad who qualified through having Italian ancestry.

This became known as the Oriundi movement. Up until the late 1920s Italian domestic football essentially had a ‘no foreigners’ rule under the Carta di Viareggio, meaning that these transfers would have to have been signed off by high ranking officials.

After a slow start for the Old Lady, Monti captained them to four successive Scudetti between 1932 and 1935 but it was 1934 which was his finest hour.

The Italian manager was Vittorio Pozzo, who is considered to be the creator of the Metodo system of playing.

Pozzo adapted the popular ‘Danubian’ system of the time (2-3-5) by moving two if the forwards back into midfield to create a 2-3-2-3.

This gave the defence more protection against stronger opponents and became the precursor for the WM system.

Pozzo recognised Monti as the perfect player in the system to feed star centre forward Giuseppe Meazza.

The Azzuri began the tournament by swatting aside the USA 7-1. The quarter-final against Spain proved to be a tougher task.

Tempers flared and both teams gave as good as they got in terms of physicality with the officials reportedly favouring the home side. It ended 1-1, meaning a reply was required.

The true effects of the Italians’ tough tackling were only realized then, with six Spanish players missing from the starting line-up for the return leg.

Another three would go off during the game as the Azzurri battled to a 1-0 victory. The officials again seemingly fine with the level of physicality.

The victory, however, questionable set them up with a semi-final tie against Austria, led by legendary coach Hugo Meisl.

Nicknamed ‘Der Wunderteam,’ this would be Italy’s toughest test yet. With help from some more favourable officiating and Monti expertly nullifying Austria’s star man Matthias Sindelar they again scraped through 1-0, setting up a final with Czechoslovakia.

Some reports at the time suggest the referee favoured the Czech team to help them beat Germany in the other semi to offer Italy an easier opponent in the final.

Pozzo with his revolutionary system and Oriundi-packed squad were just 90 minutes away from success. The closer they were the more the pressure intensified.

The day before the final a telegram arrived at the team’s hotel, addressed to the team. It read: “Victory or death gentlemen, if the Czechs are correct, we are correct, that first of all.

“But if they want to win bullying us, the Italian must hit, and the opponent must fall…Good luck tomorrow. Win. If not so, crash.”

The game started slowly, the pressure of the occasion (and potential death) perhaps getting to the teams. The first half ended 0-0.

As Italy got to the dressing room they were greeted with another note from the powers to be. It bluntly read “You are responsible for the success, but if you fail, may God help you.”

As the second half went on it seemed the advice was having the opposite effect, the Czech’s went ahead on 71 minutes.

You couldn’t begin to imagine the pressure the Italian players must have felt.

Staring down the barrel of defeat they somehow managed to turn the game around and nick two goals in 14 minutes the first from Raimundo Orsi another of the ‘Oriundi’.

The eventual winner came in extra time from Bologna star Angelo Schiavio.

After the dramatic loss four years earlier Monti had done it. He was a world champion. In years to come, he anecdotally spoke about the half time team talks he received at both finals:

“In Uruguay, they would kill me if we won. In Italy they would kill me if I lost.”

And the gratitude showed by Mussolini: “we were allowed to ask whatever we wanted: women, money, jewels, cars, house. We were the privileged human beings of Italy.”

There is a slight irony in that we now live in an age where freedom of movement between countries is a lot more prevalent and a larger number of dual nationality players exist.

But, because of the FIFA rulings on eligibility, nobody can match the unique record held by ‘Doble Ancho.’